|

More than two centuries ago the land around Boyds was parceled out in thousand-acre tracts to Tidewater planters in search of new frontiers. A handful came, bringing their retinue of tenants, servants and slaves, to grow tobacco and continue the plantation way of life.

Among the early Tidewater settlers in this area the White and Gott families stand out most prominently. The names Nicholl, Carlin, Pyle, and Hoyle also date from early times, as do the names of the black slaves who came with them—names such as Duffin, Turner, and Hawkins.

Unfortunately for these early settlers, the thin, stony clay soils of these hilly uplands were ill-suited to the kind of agriculture they sought to introduce. Yet for a century these planters persisted in growing tobacco and corn to the exclusion of other crops. The more they did so, the more quickly the soils deteriorated, until they were barely able to provide subsistence for either the owners or their labor force.

The Civil War and the end of slavery put a final end to these ill-starred attempts to mirror Tidewater plantation life. Fortunately, at just this juncture the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began construction of its Metropolitan Branch, connecting the District of Columbia with Point of Rocks via Rockville and Gaithersburg. The route chosen passed through the heart of this beautiful but impoverished countryside.

This development had the most momentous effects. It brought an influx of people. It brought new life to the dying or abandoned farms roundabout, and launched new ways of farming that ushered in the district’s most prosperous period. It transformed the previously loose-knit aggregation of tiny hamlets—Bucklodge, Blocktown, White Grounds, Tenmile Creek—into a cohesive community, and it gave the name Boyds to the new town in honor of the man who did the most to bring the miracle about.

James A. Boyd, a Scot whose leadership is often honored by the title “Colonel,” was contractor for seven of the most difficult sections of the new rail line—a line some seven miles long, stretching from Germantown across the gorge of Little Seneca Creek and then through a series of long and difficult rock cuts culminating in the one that runs from Parr’s Ridge (Peach Tree Road/Ridge Road) to Sellman (Route 109).

Boyd recognized the uplands west of Little Seneca Creek as an ideal central location in which to house the hundreds of workmen in his section gangs. Accordingly, he purchased 130 acres in what is now the center of town for this purpose, and then, seeing the potential of this area with its high open lands and vistas to the west, bought an additional 1,200 acres for his own use. Once the rail line was finished, in 1873, the B & O reciprocated by building a stylish brick station house and naming the stop for Boyd.

The railway station and the road network spreading out from it were a magnet for all sorts of new growth. Entrepreneurs James E. Williams and Mahlon T. Lewis opened the first business shortly after the first train came through; churches and schools were built. Even more important, as Colonel Boyd seems to have been the first to recognize, the railroad made it possible to haul fertilizer and other supplies and to ship milk and agricultural products to market more efficiently and cheaply. His own farm, “Bonnie Brae,” northeast of the station, became a model of progressive farming, and its example completely transformed the character of farming in the region.

The high, cool, open countryside soon began to draw summer visitors seeking to escape the heat of Washington. Boyds, Burdette, Tenmile Creek Road and Barnesville Road all boasted large Victorian houses with extra rooms for boarders. Boyds developed into a social and economic center, and both the black and white communities prospered.

The Boyds area supported both white and black schools and churches as early as 1879. While each community recognized the importance of the other, and often provided sustenance, they did not unite until the coming of school integration in 1961. Significantly, the newly integrated school, built for black children in 1952, remained named for the first African-American supervisor in the county school system, Edward U. Taylor.

These long-established close relationships continue today, as local residents endeavor to work out the problems facing their community, chiefly the struggle between encroaching development and the efforts of people who want to preserve the traditional semi-rural way of life implied by the town slogan, “Home in the Country.”

The trail along several scenic lanes is described below. It attempts to touch upon a collection of sites which figure in the area’s varied history and places of natural beauty. A few remaining traces of the old plantation life, the influence of the railroad, and relics of the bountiful years after about 1895 line the first four miles of the route and can be seen again as you must return the same way after completing the scenic loop that constitutes the second part of the tour. Due to the narrow roads and heavy traffic, we do not recommend riding along Barnesville Road west or Route 121 north of Boyds, even though they would allow a total loop. The trail as plotted here is 18 miles long and can be covered by bike in about three or four hours. The trail along several scenic lanes is described below. It attempts to touch upon a collection of sites which figure in the area’s varied history and places of natural beauty. A few remaining traces of the old plantation life, the influence of the railroad, and relics of the bountiful years after about 1895 line the first four miles of the route and can be seen again as you must return the same way after completing the scenic loop that constitutes the second part of the tour. Due to the narrow roads and heavy traffic, we do not recommend riding along Barnesville Road west or Route 121 north of Boyds, even though they would allow a total loop. The trail as plotted here is 18 miles long and can be covered by bike in about three or four hours.

1. Boyds Station

For orientation purposes, and because of its pivotal influence on Boyds history, it is best to begin at the railroad which transformed the earlier community. Park in the MARC train stop lot on White Ground Rd. just west of Route 117. (If no parking spots are available, go 0.4 mile further south on White Ground Road to the Boyds Presbyterian Church parking lot and bike or walk back to the train stop for the first tour stop.) For orientation purposes, and because of its pivotal influence on Boyds history, it is best to begin at the railroad which transformed the earlier community. Park in the MARC train stop lot on White Ground Rd. just west of Route 117. (If no parking spots are available, go 0.4 mile further south on White Ground Road to the Boyds Presbyterian Church parking lot and bike or walk back to the train stop for the first tour stop.)

Across the tracks from the train parking lot and behind the former Anderson’s Farm Supply building, one can see the platform and the foundation outline of a frame station house and associated warehouse buildings on the north site of the tracks. The original brick station house, on a platform south of the tracks, was torn down in 1928, when the line was double-tracked. The large iron building behind Anderson’s is thought to be part of Hoyle’s Mill, moved here form Little Seneca Creek in 1893. The old station platform gives a good perspective of the obvious division of the town into two distinct parts by the railroad which created it.

On high land to the west, extending over a huge area mostly to the south of the railroad, is a great area of diabase rock. It was once owned by the Rockville Crushed Stone Co., which was anxious to exploit it, since it is a valuable resource— the only such deposit in Montgomery County. Residents on all sides of the proposed quarry, fearing irreparable structural and environmental damage, fought successfully to preserve the land unchanged.

Now start the tour as you bike south along White Ground Road.

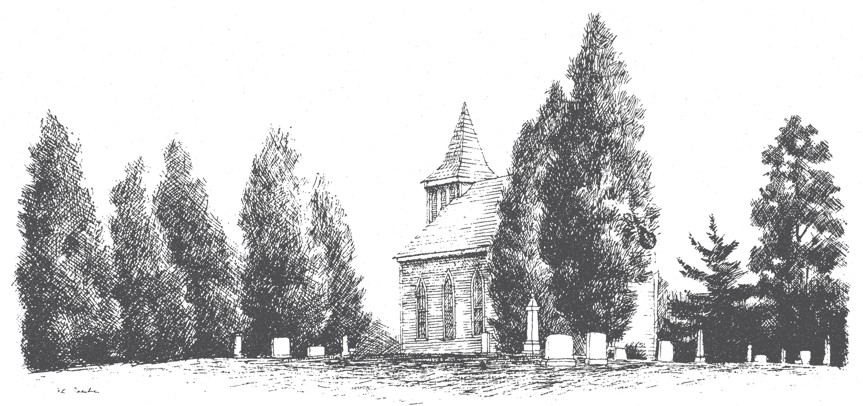

2. Boyds Presbyterian Church

The earliest settlers in the region were too few to support a church of their own, but with the coming of the railroad, the population increased dramatically. Most of the newcomers, like Boyd and others who stayed on in town after building the railroad, were Scots or Scotch-Irish, devout Presbyterians who needed their own “kirk.” The earliest settlers in the region were too few to support a church of their own, but with the coming of the railroad, the population increased dramatically. Most of the newcomers, like Boyd and others who stayed on in town after building the railroad, were Scots or Scotch-Irish, devout Presbyterians who needed their own “kirk.”

In 1874, Colonel Boyd offered substantial financial aid for constructing a church, and James E. Williams donated the land on which to build it. By 1876 the building was complete and in use, except for the vestibule and tower which were added later. The brick parsonage across the street was built in 1932 with money raised by the sale of half the Boyd farm, willed to the church by the Colonel’s widow.

As you bike southwestward down White Grounds Road you pass a number of small homes on tracts purchased gradually by members of theDuffin family from Boyd, Williams, and other big landowners. Several of these Duffin family members were former slaves or freedmen who had worked on the nearby estate of Benjamin C. Gott; others came to the area from Barnesville to work for Boyd.

3. St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church 3. St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church

This church, for nearly a century the hub of social and cultural life for African-American residents of the Boyds area, was organized before 1879 when Colonel and Mrs. Boyd sold 55 square perches of land to the Church trustees “to have and  to hold the same in trust for the colored people in that neighborhood for the purpose of holding a public school and meeting for religious worship in the building now thereon or in any building that may hereafter be erected thereon.” to hold the same in trust for the colored people in that neighborhood for the purpose of holding a public school and meeting for religious worship in the building now thereon or in any building that may hereafter be erected thereon.”

Contributions were solicited from area residents, and construction of the present building soon began. It was completed in 1893.

In 2008 the diocese closed the church and transferred its belongings to the Clarksburg church. However, members were able to re-open their church later that year.

4. Boyds Negro School

African-American children from the area attending school after the Civil War went to lessons at St. Marks, but by the 1890’s this one-room schoolhouse was in operation. The School Board paid for the materials, but it was built by local residents. It was closed in 1936, and students transferred to the larger Clarksburg Negro School. They returned to Boyds when Edward U. Taylor School was built in 1952, named for the first African-American academic supervisor of education in Montgomery County. African-American children from the area attending school after the Civil War went to lessons at St. Marks, but by the 1890’s this one-room schoolhouse was in operation. The School Board paid for the materials, but it was built by local residents. It was closed in 1936, and students transferred to the larger Clarksburg Negro School. They returned to Boyds when Edward U. Taylor School was built in 1952, named for the first African-American academic supervisor of education in Montgomery County.

Soon after passing Taylor School the cyclist descends, gently at first, into an area that is heavily wooded and overgrown. There are few habitations along this stretch of road, because this is part of the famous “White Grounds” from which the road takes its name.

Though some attribute the name to the White family whose landholdings dominated the Boyds area in the late 18th century, most connect it instead to the thin, whitish, infertile soil which weathers out of the underlying diabase rock, and turns to a peculiarly unpleasant white mud when wet. A few widely scattered Victorian farmhouses dot the landscape, and cyclists can easily imagine they are in a century past, with no modern distractions to break the illusion.

5. Buck Lodge

As you pass Old Bucklodge Lane (on your right) you cycle up a gentle rise and under high voltage power lines. Soon, on your left, you can see through the woods the ruins of the old Gott plantation house. This mansion was built in 1792 by Richard Gott of Anne Arundel County and called by him “Buck Lodge. His plantation included one of the largest tobacco farms in the area, with more than 850 acres of land and numerous outbuildings, a blacksmith shop, slave quarters, a carriage house and barns.

Benjamin Gott, son of the original owner, was a Union sympathizer, but like many other wealthy farmers of the time, he hired a former slave to serve in his place in the Union Army. Troops of both sides frequently raided the plantation during the Civil War.

The mansion once had two sections—an original structure of stone and a frame section built later, but a disastrous fire more than fifty years ago destroyed all but a corner of the stone section.

Now backtrack to the intersection of Old Bucklodge Lane and turn left (north). Soon the scrub oak and woodlots give way to open farmland. The road is a paved lane that follows angular farm boundaries on its notably scenic journey between White Ground Road and Bucklodge Road (Rt. 117).

6. The White-Carlin House

About 1.3 miles up Old Bucklodge Lane you will see a large, rectangular Georgian-style stone house on the left which was built about 1800 by Nathan White, one of the first settlers in the area. Named for its first and last individual owners, this house, like “Buck Lodge,” was the center of an early tobacco plantation worked by slaves. Notice the springhouse and summer kitchen, and the two-story bank barn which is among the largest in Montgomery County. The house is restored by the current owner. About 1.3 miles up Old Bucklodge Lane you will see a large, rectangular Georgian-style stone house on the left which was built about 1800 by Nathan White, one of the first settlers in the area. Named for its first and last individual owners, this house, like “Buck Lodge,” was the center of an early tobacco plantation worked by slaves. Notice the springhouse and summer kitchen, and the two-story bank barn which is among the largest in Montgomery County. The house is restored by the current owner.

Continue north on Old Bucklodge Lane through the grouping of houses known as Turnertown. This small African-American community was settled by members of the Turner family who had formerly been slaves or freedmen employed by local farmers and millers. Continue to the intersection of Bucklodge Road (Route 117) with Old Bucklodge Lane.

7. Community of Bucklodge

Before the coming of the railroad, this area was loosely settled, made up of plantations like Buck Lodge and the White-Carlin Farm, other farms along Bucklodge Road, and a sawmill and grist mill. The mill was built for Nathan S. White before 1816, and was sold to John Darby in 1864. John and then James Darby ran the water-powered mill until 1925. The house overlooking this intersection was the miller’s house. It is restored by the current owner.

Turn northeast on Bucklodge Road, and shortly pass under a railroad bridge. The B & O Railroad opened a station here at Bucklodge in 1885. No station house remains today and there is no longer a stop here. At one time a general store, feed store, post office, and blacksmith shop served the community, as did Darby’s mill. A house on the right just before the railroad underpass was built around 1900 for M. E. Wade, who ran the store and post office adjacent to the house. At one time the house was used as a hotel, and later as a nursing home. After long neglect, it was burned by Montgomery County.

Continue on to Blocktown, at the intersection of Bucklodge, Barnesville (sharp left), and Slidell (left) Roads.

8. Blocktown

Blocktown was a dairying community settled by African-Americans after the Civil War. Its name was derived from the method of constructing the houses using railroad crossties as a substitute for more conventional foundations. The character of the community has changed and no evidence of the original bungalows at this junction are easily visible.

Turn onto Slidell Road and cycle northward, down and up a couple of significant hills, past farmhouses that were here when the road was surveyed in 1875. Descendants of some of the original families are still living here. The woodlots, croplands and pastures are typical of rural Montgomery County. New rural “homes in the country” have also sprung up along this road in recent years. Turn onto Slidell Road and cycle northward, down and up a couple of significant hills, past farmhouses that were here when the road was surveyed in 1875. Descendants of some of the original families are still living here. The woodlots, croplands and pastures are typical of rural Montgomery County. New rural “homes in the country” have also sprung up along this road in recent years.

9. Slidell Junction

At the intersection of Slidell and Old Baltimore Roads, a small community was located at the turn of the century. The settlement had a school, post office, general store and several farmhouses. The store and post office were discontinued after a robbery and murder around 1920. Slidell School, constructed in 1883-84, was located in a horseshoe-shaped aisle of trees just south of the intersection. It was also known as Carlin’s School for several local families who sent their children there. The teacher would arrive by horse and buggy, the children on foot. The school was closed in 1925 for lack of students and was demolished in 1976. The farm buildings in the field on the northeast corner of this intersection are in disrepair, but there is interest in restoring both house and barn.

10. Old Baltimore Road

Old Baltimore Road (Known here as West Old Baltimore Road), built in 1791 is one of the earliest roads in Montgomery County. The road was the link from Ohio to the markets of Baltimore. From the early 1800’s until the coming of the railroad, and even up to the early 1900’s, Old Baltimore Road was used by local farmers to haul grain and drive cattle to the city. Even turkeys were sometimes herded along the road, and at night the herders would stop and the turkeys would roost in the trees that lined the road. Indian artifacts have been found on farmland in the area.

Ten Mile Creek Ford

Just a mile to the east of Slidell Road is Tenmile Creek. If you want a rewarding short side trip, turn right onto West Old Baltimore Road. At 0.7 mile, in the stream valley, sits picturesque pastoral land with scattered trees. Some days you’ll see cattle munching the green grass in the lush flood plain meadow of Tenmile Creek, a scene that once was common along this and other stream valleys in the area. Ride another 0.2 mile and meet the stream where the road runs into it. This is one of the few remaining country road fords in Montgomery County, though they were common a half century ago. Turn around here and return to the intersection and then right onto Slidell Road as you head north through farms and woodlands.

11. Bucklodge Forest Conservation Park

About one mile from West Old Baltimore Road, in a deeply wooded area, is the east entrance of Bucklodge Forest Conservation Park on the left. Rescued from plans to turn it into a golf course that would have threatened the water supply for this agricultural area, this land is now part of Montgomery County’s Legacy Open Space. The program is designed to conserve and steward land of exceptional value as natural or heritage resource, water supply, urban open space, trails or farmland. This Park was among the first four properties the County Planning Board purchased under this program. This entrance is the head of a trail accessible to hikers, bikers, and horseback riders.

A short distance beyond the park entrance the road dips and a picturesque pond lies on the left hand side of the road just before it crosses over a brook and ascends a hill where an overgrown old bank barn overlooks the small wetland. Another half mile brings you to the T-intersection with Comus Road, where you turn left.

12. Sugarloaf Mountain

A short distance (0.2 mile) and sharp rise on Comus Road bring you to the intersection with Peach Tree Road and a spectacular view before you. Rolling farm fields, some populated by livestock, and the foreground for this lovely view of Sugarloaf Mountain rising some 800 feet above the fields and about 3.5 miles away. It is a monadnock, a geologic term for a mountain that remains after millions of years of erosion of the surrounding land. The rugged cliffs on the summit, favored haunt of many an avid rock-climber, are composed primarily of quartzite. Covered with a variety of oak species and other deciduous trees, the mountain may appear various shades of green, rusty red, or gray, depending on the season. Sugarloaf Mountain has been registered as a National Natural Landmark because of its geological interest and striking beauty, it is an outstanding example of an admission-free privately owned scenic park. In 1925, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright was commissioned to design an elaborate automobile observation center for the top of the mountain, but that was never carried out. A short distance (0.2 mile) and sharp rise on Comus Road bring you to the intersection with Peach Tree Road and a spectacular view before you. Rolling farm fields, some populated by livestock, and the foreground for this lovely view of Sugarloaf Mountain rising some 800 feet above the fields and about 3.5 miles away. It is a monadnock, a geologic term for a mountain that remains after millions of years of erosion of the surrounding land. The rugged cliffs on the summit, favored haunt of many an avid rock-climber, are composed primarily of quartzite. Covered with a variety of oak species and other deciduous trees, the mountain may appear various shades of green, rusty red, or gray, depending on the season. Sugarloaf Mountain has been registered as a National Natural Landmark because of its geological interest and striking beauty, it is an outstanding example of an admission-free privately owned scenic park. In 1925, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright was commissioned to design an elaborate automobile observation center for the top of the mountain, but that was never carried out.

After enjoying the view, turn left (south) onto Peach Tree Road and enjoy 1.5 miles of tree covered country lane with scattered homes and the west boundary of Bucklodge Forest Conservation Park. The road then opens up with more beautiful views of Sugarloaf Mountain and farmlands and finally crosses West Old Baltimore Road again, shortly before arriving at the intersection with Barnesville Road at a stop sign. On the southwest corner of this intersection sits the Barnesville School, a small private school in a building with distinctive architecture that, while modern, may be faintly reminiscent of Byzantine arches. That’s because it was designed to house the Arabian Horse Museum, which it did until 1969, when the museum collection moved across the country and the school bought the building. Although the museum is gone, the building remains a reminder of the strong interest in Arabian horses in this region.

13. Peach Tree Road and Sellman

Peach Tree is a fairly recent name given the historical Ridge Road. The name was changed when the County decided no road name should belong to more than a single road in the county and further decided to keep the name of Ridge Road in Damascus. At one time, Peach Tree Road had four orchards and still does have two, family-owned, multigenerational fruit farms with roadside stands. These are both near the southern end of Peach Tree Road near Rt. 28.

A mile south of the Barnesville School, you will cross over the railroad on a high bridge. This is the site of several severe train wrecks in the past. It is also the highest point on the railroad between Washington DC and Brunswick. Freight train engines can be heard to strain before cresting this point on their journeys both east- and westward.

Along the top of the bank on the north side of the track you may be able to make out a faint path. It actually becomes more of a dirt road further along its half mile between Peach Tree and Beallsville Road (Rt. 109). This was once the center of a farming community and is known to this day as Sellman, though none of the commercial establishments are still there. The area was opened in 1838 with only one road coming in from the south. Once a post office and general store were here near the railroad track. The Barnesville station is still in Sellman on Beallsville Road, although the station building is not the original. The area of Sellman also included a mill, a telegraph office, a school, and a canning factory, in addition to large farms. The land of one of the early residents, William Poole, is still farmed by his descendents. The railroad borders that farm.

Cross the railroad bridge and pass the intersection with the new Sellman Road, and continue south about a half mile to White Store Road and turn left. This road winds for almost two miles among rolling hills, farms, fields with cattle or horses, and a brook that parallels and finally crosses the road just before its end at Bucklodge Road (Route 117) where a store was located until about 1970. Turn left onto Bucklodge and follow it for 0.7 mile until you get to Old Bucklodge Lane coming in from the right. Turn onto that familiar road and retrace the next four miles back to Boyds train stop. Be sure to turn left where Old Bucklodge Lane T-intersects with White Ground Road.

14. Back to Boyds

On White Ground Road, you may wish to stop at the Boyds Presbyterian Church cemetery to visit Colonel Boyd, James Williams, and Mahlon Lewis all of whom are buried here together with other pioneers of the Boyds area.

James E. Williams owned much of the land in the upper section of White Grounds Road. His farm, which burned in the 1930’s, was located nearby; he gave land to several members of his family, and they built the first large Victorian houses on the road.

James Alexander Boyd purchased a large tract of land northeast of the Station and built his grand house there, naming it “Bonnie Brae” as a reminder of his native Scotland. Once his engineering work for the railroad was done, he became a progressive, innovative farmer who revived the land by using the then-new methods of crop rotation, drainage, and fertilizing with lime and guano delivered by train. The Boyd farm complex consisted of five barns, a two-story wash house with a fireplace, an ice house and other buildings. His dairy farm was the cleanest of its day, and rapidly earned a reputation for its efficiency. At the turn of the century, the Superintendent of the U.S. Botanic Gardens wrote that the Boyd barn housed eight sleek draft horses, the dairy barn held 100 cows, the concrete floor was kept clean, and a steam engine pumped water, shelled corn, cut hay, and sawed wood. Water, pumped from a 60 foot depth, was cold enough to chill milk before daily shipments of 180 gallons were marketed. The wheat crop averaged 25 to 30 bushels per acre. By 1890 Boyd’s example had transformed the Boyds area into a garden spot with numerous similarly improved farms modeled after “Bonnie Brae.”

Seven African-American tenant farmers lived on the Boyd property. Each family had its own house, and many had their own cows. The men worked the farm, and their wives usually worked in the “main house.” Although the tenant farmers did not receive deeds to their houses, the houses and the land around them belonged to the tenants as long as they lived.

Most of Boyd’s land is now flooded by or bounds Little Seneca Lake, a reservoir for the metropolitan Washington area water supply. The dam on Little Seneca Creek was built and the lake created in 1985. The network of creeks feeding Little Seneca includes Tenmile Creek (site 10).

The little town of Boyds, and unincorporated village of about twenty houses and three businesses, grew up around the rail station which you visited at the start of the tour. One of the first facilities to appear, a necessary adjunct to the station, was a livery stable—needed to accommodate the horses and carriages of commuters, schoolchildren, shoppers and businessmen, and to carry summer visitors to their boarding houses. The little town of Boyds, and unincorporated village of about twenty houses and three businesses, grew up around the rail station which you visited at the start of the tour. One of the first facilities to appear, a necessary adjunct to the station, was a livery stable—needed to accommodate the horses and carriages of commuters, schoolchildren, shoppers and businessmen, and to carry summer visitors to their boarding houses.

At the beginning of this century the town was the gathering spot for social and economic activities and is remembered by older residents as a pretty country village with a handsome brick train station and large, gracious homes-the center of a summer colony of visitors.

To see the old hand drawn Trail Guide site maps for the Boyds Biking Trail (now out of date), please go here.

W. Hutchinson 1980

M. Coleman 1997

Bev Thoms 2010 |