Bicycling through the Seneca Countryside

Seneca – once the land of Indians; then, in the 18th century, of frontiersmen and farmers; and for much of the 19th century, of canallers and quarrymen. Today, the famous canal and sandstone quarries that put Seneca on the map have long been abandoned, and the community survives as a country store on River Road, and as scattered homes and cottages around the creek.

For thousands of years, early peoples moved through the Seneca area to fish, hunt and camp along the Potomac, followed, in time, by the historic “Indians” who planted maize and lived in palisaded villages. A 1712 map calls Seneca Creek the “Riviere de Senecards,” noting its use as a canoe route by the Senecas, an Iroquois tribe from western New York State. Others derive the place name “Seneca” from Iroquois words meaning “plenty of stone.”

As the wilderness gave way to the axe and plow in the 18th century, tobacco became the cash crop around Seneca, but eventually depleted the soil. It was followed, in the next century, by an era of grain and livestock farming that survives even today.

In the 1790’s Seneca stone was quarried and rafted eight miles down the Potomac to Great Falls, Virginia, where it was used in a “skirting canal” that enabled river boat men to bypass the falls. Construction of the C&O Canal in the 1830’s made the stone even more valuable, and the canal gave it easy passage to markets in Washington and Georgetown. With the shift to grain and the coming of the C&O Canal and the growing demand for “Seneca sandstone,” Seneca entered its industrial heyday. Grist mills and warehouses were built, a store and hotel erected to serve canal traffic, and scores of men set to work in the local quarries. For years, Seneca-built and operated grain boats, that carried wheat and flour down the canal to Georgetown and larger craft, including a steamboat, that hauled the sandstone. When first cut, Seneca stone is relatively easy to work, but hardens on prolonged exposure to the air. These qualities, plus its proximity to the canal and the popularity of “brownstone” architecture in the Mid-1800’s led to its extensive use. Seneca “brownstone,” as it was called, built the Smithsonian “Castle” on the mall in the 1840’s, the Washington, DC Aqueduct in the 1850’s, and much of Washington’s post-Civil War architecture.

By the mid-1920’s, a century later, Seneca’s industrial era was over: its inferior stone and a change in architectural taste had closed the quarries; floods and railroad competition overcame the canal. Even the local grist mill closed shop in the 1930’s – leaving Seneca to its old families and, in recent years, to pleasure boaters and fishermen, for whom many of the present facilities have been developed.

In the 1980’s the Montgomery County Agriculture Reserve was formed, protecting 93,000 acres for farmland and agriculture. This has been heralded as one of the best examples of land conservation policies in the country. For more information on the Ag Reserve, go to: https://montgomeryplanning.org/planning/agricultural-reserve/

The Seneca Sandstone Biking Trail starts in the south east corner of the Reserve, following several Rustic Roads, which have also been preserved. They are historic and scenic roadways reflecting the agricultural character and rural origins of Montgomery County. For more information on the Rustic Roads go to: https://montgomeryplanning.org/planning/transportation/highway-planning/rustic-roads/

The Seneca Sandstone Biking Trail follows several threads of a complex tapestry: the development of local canal structures from Seneca sandstone, and the milling and shipping of sandstone made possible by the canal. From the canal, a longer loop trail branches out to explore the stone’s use in homes and farms around Seneca Valley. The trail begins at the parking lot at Violett’s Lock which is on Violett’s Lock Road a rustic road established c1830-1833, off of River Road. You will see the first six stops as you ride the C&O Canal towpath.

1. Violet’s Lock

Named for Ab Violette, the last locktender, whose house has disappeared. As you face west toward Seneca, Violet’s Lock is on the right, a “liftlock” that raised or lowered canal boats about eight feet. The lock on your left is a “guard lock,” through which local grain boats were admitted to the canal. The guard lock is still used to water an eighteen mile section of restored canal, the flow of water regulated by small “wicket gates” at the bottom of the larger lock gates. Both locks were built of Seneca sandstone. North of the locks was once the small village of Rushville, where thirsty canallers and quarrymen purchased moonshine whiskey from “Aunt” Priscilla Jenkins.

2. Dam #2

Slanting across the Potomac River to Virginia at the head of the Seneca rapids are the remains of a 2500-foot rock dam, built by the C&O Canal Company from quarry waste about 1828. Now mostly rubble, it still impounds a five-mile pool (known as “Seneca Lake”) which supports heavy recreational use. Water from the pool was fed into the canal through guard lock #2.

3. Canal Ditch

Around Seneca the ditch was kept at 60 feet wide and 6 feet deep and could handle boats carrying 120 tons of cargo.

4. Riley’s Lock and Lockhouse (also called Seneca Lock)

This lock is #24, Milepost 22.8. Canallers boated day and night, sometimes shouting or blowing a horn to alert the locktender. Old timers recall “old man Johnny Riley,” the last locktender at Seneca, as one who was never caught napping: “I didn’t care what hour of the night it was, any hour of the night you went to his lock and holler … there was the lantern waving you ahead.”

The parking lot below the lockhouse was once a large basin where boats took on grain and flour from adjacent warehouses. Seneca stone is in the lock, lockhouse, and the remnants of a basin retaining wall at the northeast end of the parking lot. Informal re-enactments of the period are frequently performed at this site.

5. Seneca Aqueduct 5. Seneca Aqueduct

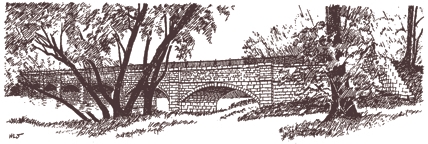

This is the first of eleven aqueducts between Georgetown and Cumberland, Maryland. In boating days, the trough was full of water and carried canal boats over the creek. On the north wall of the lock and aqueduct, look closely for the marks of the stone masons who built the aqueduct in 1829-1830.

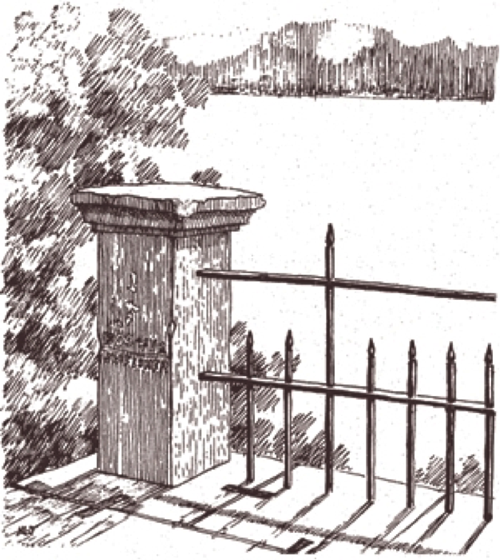

Also look for rope marks along the parapet, worn there by generations of mules and towlines. In September, 1971, a bad freshet on Seneca Creek collapsed the aqueduct’s west arch. Flood marks from the historic Potomac floods of 1899 and 1936 can be found on a sandstone post on the southeast corner of the parapet. Now take the path to the north of the canal to the turning basin. Also look for rope marks along the parapet, worn there by generations of mules and towlines. In September, 1971, a bad freshet on Seneca Creek collapsed the aqueduct’s west arch. Flood marks from the historic Potomac floods of 1899 and 1936 can be found on a sandstone post on the southeast corner of the parapet. Now take the path to the north of the canal to the turning basin.

6. Canal Turning Basin 6. Canal Turning Basin

Here boats tied up to load stone from the nearby mill. Since canal boats were over 90 feet long, occasional basins like this one were the only places to turn around. Stone shipped from this basin went to docks in Georgetown, or up canal to Point of Rocks for trans-shipment on the B&O Railroad – often carried on a steamboat especially adapted for the canal, called the “Aunt Chercy.” Continue north from the turning basin (away from the River) and follow the path to the shell of the stone-cutting mill, located at the southern end of Tschiffely Mill Road.

7. Seneca Stone Mill 7. Seneca Stone Mill

Built of Seneca sandstone about 1837 and used to cut and dress stone from the quarries just west of here. Freshly cut stone reached the mill on a narrow-gauge railroad, in mule drawn gondola cars. Water from the turning basin powered a large turbine which ran the mill’s machinery. By charging the mill rent for water from the turning basin, the Canal Company turned a small profit: in 1893, its bill to the Seneca Stone Company came to $833.33. Note the rough-cut stone in the back of the mill, then the smoother cut stone in the front. As the mill grew, machined, rather than hand cut, stones were used. Just west of the mill are a series of overgrown quarries, developed from the high, sandstone bluffs. This deposit, which underlies most of western Montgomery County, is Triassic Age (about 200 million years ago) and is part of a larger formation that runs erratically from Connecticut to the Carolinas. Now cycle up Tschiffely Mill Road (gravel), a rustic road running along the course of the small gauge railroad which once carried grain south from the grist mill to a loading platform at the canal, and stone north from the mill to River Road.

8. Tschiffely Mill Site (pronounced Shif-fay-lee)

Mills near the intersection of Tschiffely Mill and River Roads date back to 1780, about the time local farmers began to experiment with wheat. The last mill was run by the Tschiffely family from 1900-1931 and was removed with the realignment of River Road in the 1950’s. Foundation stones for the mill were from the quarry. You will find the overgrown Tschiffely Mill race about 100 feet east of Poole’s Store, across River Road, the next stop.

9. Poole’s General Merchandise Store 9. Poole’s General Merchandise Store

The store was built in 1901 by Frederick A. Allnutt who previously owned a store along the canal in Seneca. Can you picture counters on either side of the room and a pot-bellied stove in the middle? The store’s interior looked exactly like that until remodeled in 1963. It is now owed by Montgomery Parks, acquiring the property and surrounding buildings in 1976.

In 2010, Poole’s Store closed for business. Montgomery Parks rehabilitated the store in 2019. As part of the rehabilitation, an archaeological investigation was done, uncovering many artifacts from the 18th century, as well as remnants of a stone mill pit in operation during the Revolutionary War.

As of March 2020, the feed store for animals is open, and the General Store is open at various times. For more information on the history go to https://historicalmarkerproject.com/markers/HM1T9M_seneca-store-historical_Poolesville-MD.html.

10. Allnutt House

This large white frame house was constructed in 1855 by Upton Darby, a prominent figure in the Seneca area. The Frederick Allnutt family purchased the home from Darby in 1900. Montgomery Parks also acquired this house in 1976.

Now follow Old River Road west, a rustic road that was used until the new bridge was built in the 1950’s. Turn right off of Old River Road onto exceptional rustic Montevideo Road. As you come down to Dry Seneca Creek, note the pony truss bridge. Originally built in 1910, it was beautifully rehabilitated in 2019.

On your right after the bridge is Rocklands Farm.

11. Rocklands 11. Rocklands

At the turn of the century, this house was the showplace and social center of the prosperous agrarian community. It is an excellent example of local sandstone use, showing fine joining of the sandstone. Rocklands was built in 1878 for Benoni and Emily Allnutt, members of two old and influential families (Allnutt and Dawson). The large two-story residence of Italianate design has five bays, a hip roof and two flush gable chimneys at each end. A smaller wing with a gallery porch is attached. Seven of the original outbuildings remain on the farm: corn crib, bank barn, slave quarters, blacksmith shop, smoke house, spring house and large shed. Rocklands is one of the very few fine houses of the period that can still be see unaltered in any way. It was described in 1882 as “a handsome architectural specimen” and it remains so today.

Today Rocklands Farm Winery is owned by the Glenn family, who embrace their responsibility as stewards of the land and caretakers of the historic buildings found there. You are welcome to visit! https://www.rocklandsfarmmd.com

12. Bank Barns

A number of bank barns, similar to the one on Rocklands Farm, exist in the area. A bank barn is a structure built into the side or slope of a hill, thus providing direct access to both the upper and lower levels. The upper level was usually used to store animal feed and equipment. The lower level housed the animals.

13. Stone Wall

A vivid example of one use for Seneca sandstone will be on your left before the next bend in Montevideo Road. Now turn left onto exceptional rustic Sugarland Road, where it becomes a Politician Road for a short distance. Politician Roads are one lane, cement roads, typically the first roads paved for automobile use. These roads nearly always led to the gate of a person with political influence and ended there. Turn left again onto Partnership Road. Continue down Partnership Road and turn left onto River Road. Ride carefully, staying on the shoulder, because of high-speed traffic on this road.

14. Seneca School House

This one-room schoolhouse, built of Seneca sandstone, was constructed sometime prior to 1866 when the 1st class was conducted. Land was donated by Upton Darby, owner at the time of local Seneca Ford Flour Mill. Labor and other support was provided by local families. The schoolhouse consists of two sections: the front vestibule was used for the storage of coats and lunch buckets; the larger room served as the classroom. The school ceased operation in the early 1900's with the opening of Seneca Mills School. Stones next to the Schoolhouse were likely excess product from the Seneca Sandstone Mill. Seneca Schoolhouse Museum is operated by Historic Medley District, Inc. Re-enactment classes for children are conducted by a teacher wearing 1880's style clothing. The building is usually open to the public during Heritage Montgomery Days. Bookings and other information are available by contacting info@historicmedley.org.

15. Montevideo

In 1825, Mr. J.P.C. Peter, the great grandson of Martha Washington, built this house (on your left far down a private driveway.) The Peter family owned the Seneca sandstone quarry and numerous tracts of farmland in the area. The house provides a beautiful example of federal style architecture. Continue down River Road and turn right again onto Violett’s Lock Road, which was established in the early 1830’s.

16. Seneca Community Church Cemetery

On the hilltop to your left, off rustic Violette’s Lock Road, is the cemetery that was established as much as 125 years ago by former slaves who worked in the sandstone quarries. The Potomac Grove Colored Methodist Episcopal Church once stood here, along with a schoolhouse. In 1941, the congregation built a new church on Berryville Road, near where many descendants now live.

To see the old hand drawn Trail Guide site maps for The Seneca Sandstone Biking Trail (now out of date), please go here. N. and R. Roselli, E. Wesely 1978

S. Benedict, A. Prichard 1997

John Menke 2010

Jane Thompson, Dan Seamans, Kurt and Norma Rowan 2020 |